- Pronunciation: kly-tehm-NEHS-truh

- Origin: Mycenae or Argos, Greece

- Role: Varies according to different sources, including Oresteia and Odyssey

- Related Characters: Several, including Leda (mother), Tyndareus (father), Helen of Troy (sister)

- Related Myths: Helen of Troy, Achilles, Illiad, Odyssey, Oresteia

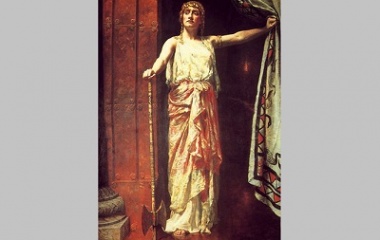

Who is Clytemnestra?

Clytemnestra is the daughter of the King and Queen of Sparta. Her siblings are Castor and Pollux, said to be the twins pictured in the constellation Gemini, and the famous Helen of Troy, whose face launched a thousand ships

Those ships were launched by Clytemnestra’s husband, King Agamemnon. After Helen disappeared across the sea to Troy, her husband asked his brother Agamemnon to help him retrieve her. Whether Helen left her husband willingly or was forcibly kidnapped by the Trojans varies by source.

Unlike her famous siblings, Clytemnestra was doomed to an unhappy life and a bad reputation. She is best known for her role in the murders of both her husband Agamemnon, and the Trojan princess Cassandra, whom he had brought back as a prisoner of war.

Though Clytemnestra was viewed as an agent of evil because of the killings she committed, it is easy for modern audiences to sympathize with her when they’ve heard the whole story.

In most versions of the myth, Agamemnon is Clytemnestra’s second husband. He married her by force after killing her first, and chosen, husband, and in some versions also killed the infant son she had with her first husband.

Years later, he tricked Clytemnestra into thinking he had arranged for their daughter, Iphigenia, to marry Achilles. But when Clytemnestra sent the girl to him, he killed her as a sacrifice in order to procure favorable winds to send his war fleet to Troy.

Armed with the winds blowing in his favor, Agamemnon took his thousand ships across the sea to fight a bloody 10-year war against the Trojans.

In his absence, Clytemnestra took a lover named Aegisthus. Aegisthus had his own grievances against Agamemnon: Agamemnon’s father had killed Aegisthus’ uncles and brothers. As a result, Aegisthus had vowed to kill Agamemnon and take the throne from him.

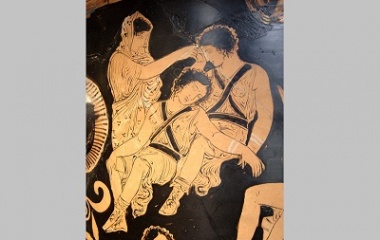

By the time Agamemnon returned from war, Clytemnestra and Aegisthus were ready for him. Between the two of them, they conspired to kill Agamemnon by entangling him with a net and then stabbing him while he bathed.

In some accounts, it was Clytemnestra herself who killed her husband to avenge her daughter (and possibly first husband and infant son). In others, it was Aegisthus who did the killing, with Clytemnestra’s permission, in order to procure the throne.

Versions of the Myth

Homer

In Homer’s account, developed in the epic poems Illiad and Odyssey, Clytemnestra played a passive role in Agamemnon’s death, merely permitting her lover, Aegisthus, to murder Agamemnon.

In this version, Aegisthus is portrayed as an unmanly coward who was one of the few Greek men to refuse to join Agamemnon’s fleet and fight the Trojans.

In this narrative, the driving force of Agamemnon’s death is Aegisthus’ desire to avenge his brothers and uncles, and take the throne which he believes belongs by right to his family.

Orestia

In the play Oresteia, written by Aeschylus, Clytemnestra is the motivating force who plans to kill Agamemnon to avenge her murdered family members. She commits the killing herself, with a double-edged axe called a pelekus.

Clytemnestra kills Agamemnon using the same method that would be used to sacrifice an animal to the gods: three blows, with a prayer to the gods uttered before striking the third. This is doubtless a reference to the sacrificial killing by Agamemnon of their daughter.

In this version, Clytemnestra also plays the active role of peacekeeper after Agamemnon’s death. She uses her axe and compelling words to prevent fighting between her lover and the Greek elders as her lover takes Agamemnon’s throne, telling them all that enough blood has been spilled.

Themes

Revenge

The myth of Clytemnestra is part of a complex web of narratives about the potentially endless cycle of revenge.

In the myth of Clytemnestra, Agamemnon is murdered as revenge for killing Clytemnestra’s daughter (and in some accounts, her first husband and infant son), and for his father’s killings of Aegisthus’ family.

Later chapters of Aeschylus and Homer’s epics cover the attempts of Agamemnon’s children to avenge their father by killing Clytemnestra.

These stories, like the story of Clytemnestra, question whether Agamemnon’s killing was a matter of righteous justice, or treachery and revenge.

Gender Roles

The varying myths of Clytemnestra and Aegisthus, which portray them either as wicked agents of evil or righteous agents of vengeance, are also heavily influenced by Greek perceptions of gender roles.

In Homer’s version, Aegisthus is viewed as an unmanly coward because he does not accompany Agamemnon’s fleet to fight the Trojans. Clytemnestra, likewise, is portrayed as wicked because she violates her vows to Agamemnon by taking a lover in his absence.

In this version, Aegisthus, as a man, is the driving force behind the story and behind Agamemnon’s death. Clytemnestra plays only a passive role, permitting herself to be seduced, and permitting her husband to be murdered.

Questions about the nature of women and the legitimacy of their agency lie at the very heart of the Trojan War myths. The war is sparked when Helen, the wife of Agamemnon’s brother, disappears to Troy. But whether Helen was abducted by the Trojans or chose to go with them varies by account.

Agamemnon’s leadership of the Trojan War then, can variously be seen as an attempt to rescue a kidnapped woman, or as an attempt to forcibly reclaim a woman for his brother, whom she had left.

The plights of other characters in the Trojan War also explain the Greek definition of “manliness” as related to willingness to fight in battle, and the Greek ideal of women as being loyal and obedient to their fathers and husbands.