- Pronunciation: tuh-lem-uh-kuh-s

- Origin: Greek

- Home: Ithaca

- Parents: Odysseus, Penelope

- Spouse: Circe, Nausicaa, Polycaste

- Children: Latinus, Persepolis, Poliporthes

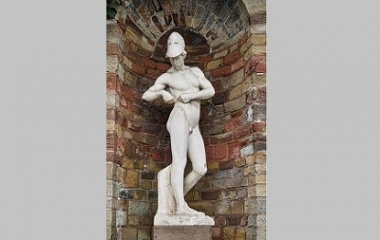

Who is Telemachus?

Telemachus was the son of Odysseus and Penelope, born in Ithaca just prior to the Trojan War. Perhaps because of this, or perhaps despite it, his life was filled with trials and tragedies from the time he was an infant.

Origin

As the son of Odysseus, a contentious character who was involved in many of the relevant plots, schemes, and adventures of his day, Telemachus’ life began in turmoil. It was not long after his birth that King Agamemnon demanded of Odysseus that he honor the oath he had sworn, and join him in sailing against Troy to retrieve Helen. When Odysseus attempted to break that vow by acting like a madman, Agamemnon’s man Palamedes threatened to murder Telemachus if Odysseus did not honor his commitment. Under this threat, Odysseus had no choice but to relent.

Family

While his father was off fighting the Trojan War, Telemachus became the “man of the house” by default, as his mother Penelope waited for his father to return. But Odysseus fought for a grueling ten years, and then was not able to find his way home. When another ten years passed, however, there was a great push for Odysseus to be declared dead, allowing Penelope to be married again and robbing Telemachus of his heritage.

History

The Suitors

As word spread that Telemachus’ mother was being courted, many suitors appeared, quite a few of which were hardly older than Telemachus himself. This did not matter to those courting Penelope, who saw a way to usurp the estate of Odysseus, thereby robbing Telemachus of his inheritance.

They initiated their presence on the estate, claiming they were forced into such action because Penelope never ventured beyond its walls. How else could they court her, other than by becoming freeloaders living off the will and finances of what would otherwise have belonged to Telemachus.

Penelope, for her part, never gave up on Odysseus and stalled the suitors by saying she could not marry until completing her husband’s shroud. She would weave by day while the suitors would eat, argue, fight, and otherwise live the life of bums at the cost of Telemachus and his family. But in the evening, Penelope would undo the day’s work, thus never completing the shroud.

Heavenly Intervention

All of this tragedy was devised by Poseidon, who held wrath for Odysseus for his involvement in the death of Poseidon’s son, Polyphemus. But as one god finds someone in disfavor, another will find favor, or in this case, pity.

Athena appeared to Telemachus in the form of the Taphian stranger, advising him to have the suitors removed by calling a council of the Ithacan lords. She also advised Telemachus to seek information regarding his father’s fate and to act appropriately. If Odysseus were alive, she advised Telemachus, then he could tolerate the suitors for a bit more, allowing Odysseus to see to them. But if he were dead that Telemachus should resign to that, build a funerary for him, and see that his mother went to an appropriate spouse. Regardless, she advised, that as an adult he must see to the removal of the current suitors, as they in their greed were worthy of only death.

Telemachus took this advice to heart, coming into maturity in that moment of resolve. And while Athena could have also informed Telemachus that his father was alive, it was important that he make this journey to find not only his father but also himself.

The Quest

First, though, Telemachus called the council. Unfortunately, many of the suitors that plagued Penelope and Telemachus were the sons, nephews, and cousins of the Ithacan lords. They chose to not see the suitors as an imposition, so Telemachus was left with no recourse.

He announced his journey to seek his father and warned the suitors that there would be hell to pay when he returned, one way or another. At first, they did not believe the boy from a few days before had become a man, but then they became fearful and cowardice caused them to sue for peace.

Telemachus would have none of it, and with Athena’s help commissioned a ship and crew for his journey to Pylos and Sparta. He first visited King Nestor, who could give him no information but advised him to visit Menelaus in Sparta.

Menelaus recounted a tale that while two heroes had died in the war, Odysseus was held the prisoner of Calypso. Knowing now that his father was very likely alive, Telemachus set off for home. He knew that every day away was another day the suitors would deplete him, or worse convince Penelope to marry them and run off with the wealth he was due.

The Return

Wisdom comes to those who welcome it, and Telemachus was wise to set forth home. The suitors were plotting against him, having realized Telemachus would never be a child of their whims again. Athena advised him to sail by night and travel on foot for the final leg of the journey, avoiding a trap the suitors had set for him.

Odysseus was also close to home, and Athena once again intervened. She disguised him as a hermit looking for a handout. While he was in the hut of his servant Eumaeus, who did not recognize him, Telemachus arrived. They had a long conversation over many things, and when Telemachus briefly left the hut, Athena removed the disguise.

Telemachus was ecstatic when Odysseus identified himself. Together the two men began to plan the fate of the suitors. Telemachus would sneak in and remove all weapons that were not immediately at hand to the suitors. Odysseus would then appear, again as a beggar, and confront them.

As it played out, Odysseus took his revenge with his own bow, which none of the suitors had been able to draw. The battle was over almost before it had begun, thanks to Telemachus’ retrieval of the weapons and the suitor’s surprise at being assaulted by what they believed to be a beggar.

When the king of Epirus, as arbiter in the ensuing dispute, determined that Odysseus had gone too far he exiled him, making Telemachus the immediate true heir to the estate and the ruler of Ithaca. The suitor’s relatives were ordered to compensate Telemachus for what the men had done, and thus Telemachus’ wealth was restored as well.

Marriage, and Children

As the ruler of Ithaca, and with the business of restoring his estate behind him, Telemachus settled into the matters that come with becoming a man. In his life he would marry three times, producing one offspring with each of his three wives. The first was Polycaste, daughter of King Nestor who had met Telemachus when he was in Pylos. Their son was named Persepolis. Later, with Circe, he would have another son, Latinus, who would go on to rule Latium. Finally, Telemachus had a daughter, perhaps as completion of an unfulfilled prophesy that Odysseus and Penelope would bear one, named Poliporthes with the Phaeacian princess, Nausicaa.