What is the Beast of Gévaudan?

The Beast of Gévaudan was a monstrous, wolf-like creature who turned the mid eighteenth century into a terrifying bloodbath for the people of Gévaudan, a small province in south-central France. Although the Beast claimed 80-200 lives and left numerous eye witnesses in the wake of his attacks, he was never positively identified as any known predator. To this day, he remains one of history’s bloodiest mysteries.

Characteristics

Physical Description

Eye witness accounts of the Beast yield a motley specimen, a patchwork of traits from wolves, lions, hyenas, bears, dogs, and panthers.

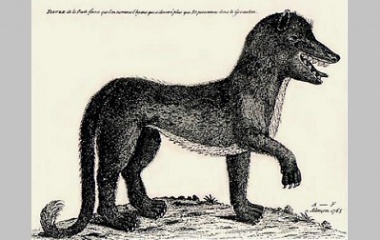

By all accounts, the Beast was huge. Many witnesses compared it to a small horse or a calf. The Beast’s hair varied in color. Usually, its base coat was reddish-brown, but its markings varied from a black stripe down its spine to patches of gray hair to spots on its hindquarters. It had long, vicious fangs and claws unlike any of the known predators in the region. Some witnesses claimed that the claws had melded together into a sort of hoof. The Beast’s head was flatter and its snout was more pig-like than a wolf; it’s ears were small and round. It had a wide, cavernous chest, narrow hips, and a long tail, thin but terribly powerful. According to some witnesses, the Beast could use its tail as a weapon to knock men off their feet.

Hunters produced as many as six different bodies, claiming that they had slain the Beast. These bodies were usually around 150 pounds and resembled very large wolves. The two most credible bodies were stuffed, examined by surgeons, and even presented at the royal court. One of the bodies was described by a famous wolf-hunter, who said,

“We declare by the present report signed from our hand, we never saw a big wolf that could be compared to this one.”

The other body was described by the superintendent of Gévaudan’s region, who reported that

“a native killed an animal which appeared to be a wolf, but a wolf extraordinary and quite different by his figure and his proportions from the wolves that one sees in this country.”

Behavior

The Beast was feared not just because of his terrible power but also because of his unusually brutal hunting techniques. Although he did prefer to attack victims when they were alone, he was clearly unafraid of adult humans, being six times more likely to attack an adult than your typical wolf. His attacks were almost always a surprise; he would appear suddenly from the bushes or even drop down on his victims from above, and he seemed to prefer broad daylight to the typical predator’s cloak of night. He used his claws to devastating effect, much more so than typical wolves, but his signature deathblow was to tear out his victims’ throats or crush their skulls. Chillingly, the Beast seemed to hunt for pleasure as much as hunger. Although he sometimes devoured victims, he killed them and abandoned their carcasses just as often.

Over time, the Beast proved to be equally talented at playing “the hunted” rather than “the hunter.” He was a master of evasion; just when hunters thought they had him cornered, he would disappear. He also seemed to be unaffected by bullets. According to several hunters, he suffered multiple gunshot wounds, only to rise and escape back into the bushes.

Many local people in Gévaudan believed that the Beast had helpers in his dirty work. Some of his victims were killed at the same time in different locations, and some witnesses reported seeing him in the company of his mate, his cubs, or even a man. This last report, coupled with the fact that the Beast was sometimes seen wearing armor made out of tough hog skin, led some villagers to believe that he was a trained attack animal, rather than a lone predator.

History

Killings

The Beast’s paws are bloodied with the death of 60-200 men, women, and children in the region of Gévaudan.

His first attack took place in the summer of 1764, when he charged a woman who was out tending to her cattle. Fortunately, the woman’s herd included several bulls, who managed to fend off the Beast, but the his next victim, a 14-year old child, was not so lucky.

Within months, the monster had claimed so many lives that mass hysteria began to set in. The hysteria was fueled by the Beast’s reputation for striking anytime, anywhere. Although he preferred lone shepherds, he was also documented attacking villagers while they worked in public gardens, shoppers at the great spring fair, and even priests and monks in an abbey.

Public hysteria reached a climax in 1765, when the Beast attacked a group of seven armed men. Although the men survived, the audacity of this attack brought the Beast to the king’s attention, and he launched a crusade to end the bloodbath. Despite the king’s wrath, the Beast’s reign of terror would continue until June 19, 1767.

Hunts

Soon after the Beast’s killing spree began, local men began taking up arms against the monster that plagued them. In less than six months, these men had declared all-out war against the local wolf population, forming large hunting parties called “beats.” In total, these hunting parties would kill over 100 wolves before the hysteria subsided.

In October of 1764, Captain Duhamel organized his soldiers into one of the largest hunting parties that ever trailed the beast. Fifty-seven men took on the project, but the Beast evaded them all. Their failure, however, only served to excite other hunters across the nation. Soon, a reward was being offered for the Beast’s pelt, and hunters were flocking into the region of Gévaudan to join the sport.

Among the hunters pouring into Gévaudan in the summer of 1765 was Denneval, a famous wolf-hunter sent by the king. Denneval brought his legendary bloodhounds to track the beast, but after witnessing the death of several men, Denneval fled the province.

Finally, the king sent his own personal gun-carrier, François Antoine, to bring the Beast to justice. For months, Antoine merely studied the landscape and the monster’s habits. Then, on September 20, 1765, Antoine and a party of 40 men and 12 bloodhounds brought the monster to bay near the Abbey of Chazes. Incredibly, the Beast survived a first volley of bullets and staggered back to his feet, ready to attack again, but the second volley brought him down for good. His body was stuffed and presented to the king in his royal court.

For three months, the countryside enjoyed a break from the grisly killings that had plagued it for over a year. Then, in December of 1765, the Beast (or a new beast) emerged to paint a bloody sequel to his rampages. This monster continued killing well into 1767, when a party of 300 hunters finally sent him to his grave. Among the hunters was a local farmer and inn-keeper, Jean Chastel, who encountered the Beast alone and fired two silver bullets into its chest, thus silencing it forever.

Art and Literature

During the Beast’s reign, numerous artistic renderings were made of him, both to warn the public about him and to aid hunters in identifying him. He was a regular character in newspapers and wanted posters.

Since his demise, the Beast has become a famous figure in werewolf lore. He made his literary debut with gothic novels like La Bête du Gévaudan and Wolves: An Old Story Retold. Since then, he has been handed down into contemporary werewolf media, such as the feature film Brotherhood of the Wolf and the TV drama Teen Wolf.

Explanations of the Creature

Perhaps even more than he grips the imagination of paranormal fiction fans, the Beast fascinates historians and cryptozoologists. Unlike other “mythical” creatures, the monster who ravaged Gévaudan comes with a solid historical record. There’s no doubt that something was responsible for all the carnage, and scholars love to speculate about the true identity of that something.

Until recently, the most popular theory explained the Beast as a wolf-dog hybrid. If a wolf mated with a large dog (mastiffs were popular during that era), the offspring might have had several of the Beast’s traits, namely his size, his thin tail, and his reddish coat. He might also have had the Beast’s peculiar disposition, which combined a wolf’s predatory bloodlust with a dog’s lack of fear of humans.

More recent evidence has pointed to a striped hyena or a pack of striped hyenas. Although striped hyenas had been driven out of Europe long before 1764, they were not uncommon in “menageries,” collections of wild, exotic animals kept by eccentric individuals. Jean Chastel’s own son was said to keep hyenas in a menagerie near Gévaudan, and stuffed hyenas, dating back to the early eighteenth century, have been found in nearby museum collections. Although the striped hyena certainly isn’t the size of small horse or a calf, its stripes, broad chest, and flat head match physical descriptions of the beast. The popular cryptozoological TV series, Monster Quest, helped to popularize this theory.

National Geographic has also weighed in on the mystery of the Beast. In September of 2016, they named a young, male lion as the culprit, claiming that the lion was a perfect match for the Beast’s physical description and hunting style. Lions can weigh up to 800 pounds, almost ten times as much as a wolf. They have reddish-fur and, when young, might have stripes down their backs or spots on the haunches. Their tails are long, thin, and tasseled, and their heads are flat with small, round ears. They are experts in stalking prey without being seen, even in broad daylight, and they frequently leap on their victims and crush their throats or heads.

Perhaps the most chilling theory is that the Beast was more than a predator. He may have also been a pet. The fact that the beast killed without eating his victims and was sometimes seen wearing “armor” or in the company of a man suggests that he might have been trained to kill. Many scholars have pointed fingers at Jean Chastel, whose heroism was celebrated after he was mysteriously able to kill the beast, when dozens of other famous hunters had failed. It’s known that Chastel’s son kept a menagerie, so he would have had access to wild animals. Chastel’s character is also called into question by his imprisonment, during the 1760s, for misleading some of the king’s men into a swamp, where they almost died. Chastel may have been motivated to breed and train the Beast as a cover-up for his own murderous impulses, or he may have used the Beast as a way to gain personal glory, while also reducing the wolf population that preyed on his sheep.